Mathematics Awareness Month 2014: Mathematics, Magic, and Mystery

Navigate the Calendar

Martin Gardner: The Best Friend Mathematics Ever Had

Today we take some time to celebrate the mathematical legacy of prolific writer Martin Gardner (1914–2010), who has been called “the best friend mathematics ever had.” In a sense, April 21 is his 199th half-birthday, since October 21, 2014, will mark 100 years since his birth. Much more information can be found on the Martin Gardner Centennial webpage.

Here’s an excerpt from a 1996 episode of The Nature of Things made by David Suzuki, in which Martin decribes how he got started with hexaflexagons.

And here is the full 46-minute Mystery and Magic of Mathematics: Martin Gardner and Friends episode of The Nature of Things. It is a fitting tribute to Martin’s numerous passions, and a reminder of the incredible web of mathematicians, magicians, puzzlers, and skeptics that he informally assembled and mentored over the decades.

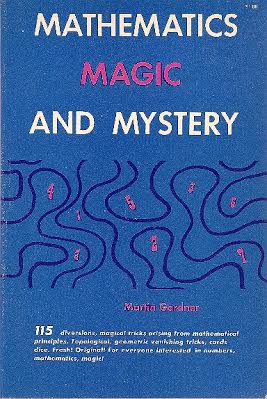

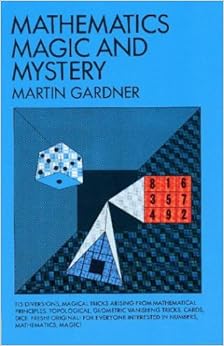

Mathematics, Magic, and Mystery

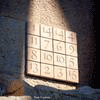

Martin’s book Mathematics, Magic and Mystery (Dover, 1956) launched his career of bringing fun mathematics (and math-based magic) to the general public. Of course, that volume inspired the theme and spirit of Mathematics Awareness Month 2014, which echoes many of Martin’s favorite topics: magic squares, braids, knots, geometric vanishes, Möbius bands, illusions, and magic with cards.

Soon after that book appeared, Martin started writing a remarkable monthly column for Scientific American called “Mathemagical Games.” There, for over twenty-five years, he entertained and inspired millions of readers with elegant mathematical gems and puzzles. Through his roughly 300 “Mathematical Games” columns, many people all over the world first learned of hexaflexagons, polyominoes, the Soma cube, pentominoes, rep-tiles, tangrams, the art of M. C. Escher, origami, Conway’s Game of Life, Penrose tiles, fractals, RSA cryptography, and much more. Thanks to the MAA, seven classic “Mathematical Games columns” are available online, as they appeared in later books.

Mathematical Martin

Amazingly, considering his reputation and influence in mathematical circles, Martin Gardner wasn’t a traditional mathematician. In fact he famously never took any math classes past high school, which in his day meant that he never learned calculus as a youth. Hence, he never assumed that his readers knew any calculus, though he later learned the subject on his own, publishing Calculus Made Easy (St. Martin’s, 1998) when he was in his 80s.

Martin’s very first writing about mathematics goes back to the 1940s, a science fiction story with a topolgical twist called “The No-Sided Professor” (it’s now available in a collection). There soon followed a series of articles in Scripta Mathematica, describing math-based card tricks and topological magic. He didn’t publish his first article in a refereed mathematics journal until 1989, but in the interim, his other writings on the subject had secured him a place of high respect among mathematicians.

Martin was a firm believer in the power of fun and recreation in mathematics, and the value of the “Aha!” moment of discovery. In the introduction to his book Mathematical Carnival (Knopf, 1975), which is available as part of the searchable CD-Rom Martin Gardner’s Mathematical Games: The Entire Collection of His Scientific American Columns (MAA, 2006), he wrote:

“Surely the best way to wake up a student is to present him with an intriguing mathematical game, puzzle, magic trick, joke, paradox, model, limerick, or any of a score of other things that dull teachers tend to avoid because they seem frivolous.”

In the informative 32-page booklet that accompanies the CD-rom, he is quoted:

“I enjoy mathematics so much because it has a strange kind of unearthly beauty. There is a strong feeling of pleasure, hard to describe, in thinking through an elegant proof, and even greater pleasure in discovering a proof not previously known.”

Magical Martin

From an early age, Martin Gardner was a keen magician, though he was never a professional one. He published in the field for 80 years, starting as a teenager a quarter century before he wrote Mathematics, Magic and Mystery. He was listed in the “100 Most Influential Magicians of the Twentieth Century” by MAGIC magazine in 1999, and he received the “Lifetime Achievement Award” from the Academy of Magical Arts, the Magic Castle, Hollywood, CA,in 2005.

Mysterious Martin

Martin Gardner was fascinated by paradox and mystery, both in fields of entertainment such as conjuring, and in relation to The Big Questions of Life, such as those that arise in philosophy (which he studied at the University of Chicago), science (the origins and nature of the universe) and religion. He came to what some may view as a paradoxical conclusion, as magician Teller relays in his NYT review of Martin’s memoirs:

“Gardner, like a human Möbius strip combining the faith and skepticism of his parents, explains that he believes in God.”

In a 1998 interview with Kendrick Frazier, Martin indicated that he considered himself a mysterian:

“I believe that the human mind, or even the mind of a cat, is more interesting in its complexity than an entire galaxy if it is devoid of life. I belong to a group of thinkers known as the ‘mysterians.’ It includes Roger Penrose, Thomas Nagel, John Searle, Noam Chomsky, Colin McGinn, and many others who believe that no computer, of the kind we know how to build, will ever become self-aware and acquire the creative powers of the human mind. I believe there is a deep mystery about how consciousness emerged as brains became more complex, and that neuroscientists are a long long way from understanding how they work.”

Skeptical Martin

Rationality and the debunking bad science were other longterm interests of Martin’s; he was first and last a skeptic. His targets included creationism, UFOs, and crop circles. Indeed, for many his written skeptical legacy rivals his mathematical one.

Martin Gardner Was the Best Friend Alice Ever Had

Martin’s best seller by far was The Annotated Alice (Potter, 1960) and its later incarnations. In a 2005 interview with Don Albers, he commented:

“[I]t has sold more than a million copies if you include paperbacks and translations. It has never been out of print.”

Martin was a huge lifelong fan of both Alice in Wonderland and the Wizard of Oz, and he published many annotated editions of works by Alice author Lewis Carroll—who was a mathematician in real life, and who buried insider mathematical references in his writing for children—and other authors.

The Nature of Martin Gardner